For my recent Band of Blades game, I decided to write up “mission overviews” as a GM’s play aid before each game, for each of the (usually three) missions, with narrative details and information about the mission, enemies, obstacles, etc. And, of course, the graphic designer part of me couldn’t help but gussy them up.

Now, you can simply run missions off-the-cuff immediately after rolling them (and I believe this is the way you’re supposed to do it — or as they say, the RAW), but I find I prefer at least some prep before play. I’ve found those missions I don’t prep for, at least to me, feel less exciting and have less narrative “fullness”. YMMV, of course.

But for folks like myself, or anyone who enjoys reading over what other groups have done, perhaps to stir their own creative well, or, I guess, to play vicariously even, please enjoy the following. And, hey, if you use any of these missions in your own game, or variants of them, I’d love to hear how they went, such as how you changed them, how your players approached the problems, and how it all turned out!

I have almost an entire campaign’s worth of mission sheets — however, I didn’t write up the opening mission (included in the book), the last few phases of play (was very busy), or the Skydagger Keep missions (doesn’t need this extensive a treatment and are handled differently in play). There are around ten completed sets in total. I have converted most of the sheets I do have to .pngs and filled in some missing details to make them more useful to others. The specific blog posts usually include information on how our group fared on these missions and notable events or choices involved.

If you are interested in reading how these missions went for our group, and the entire story of our campaign, you can find it on the (archive.org archived version) of the BitD community boards in this series of posts:

New Group, First Mission, Zora AAR

More Adventures of Zora’s Legion

More Adventures of Zora’s Legion: Half-way Through the Dark

More Adventures of Zora’s Legion: Skydagger Keep!

General notes on these missions »

Owing to the nature of

Band of Blades, these aren’t “generic” missions you can simply drop into any campaign; they were written for a specific play group and specific campaign, with its characters and narrative history. For example, the group chose Render and Breaker as their Broken foes, with Zora as their Chosen. Thus those Broken, and their subordinates, and that Chosen are referred to throughout.

Various choices and successes (and failures) during the campaign altered the nature and composition of the missions, the types of enemies faced, the number of phases spent in a particular location, and so forth as the campaign advanced, including some missions the players designed themselves and declared the Legion was pursuing.

That said, most (all?) of the missions should be able to be converted to another campaign with minimal work, while others might best be used as creative fodder.

Explanation of the sheet design »

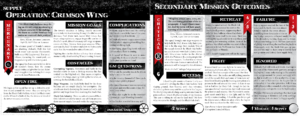

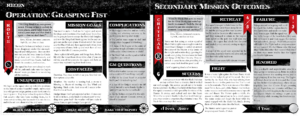

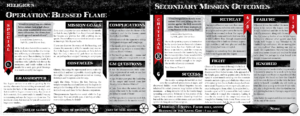

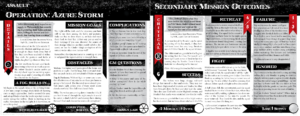

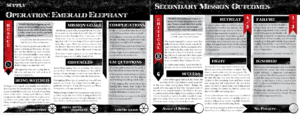

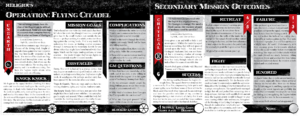

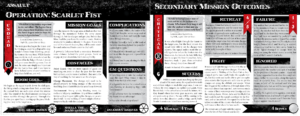

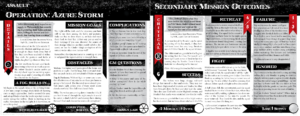

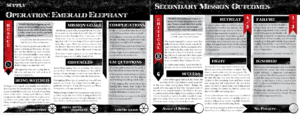

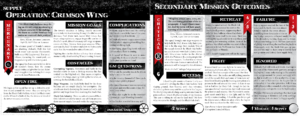

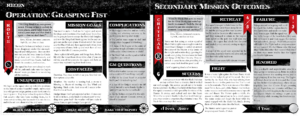

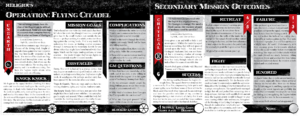

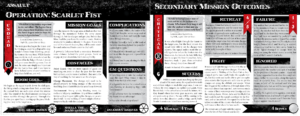

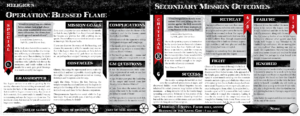

Much of the sheet should be pretty self-explanatory. On the left, you have a description of the mission and some useful details if running it as a primary mission; on the right, you have the details of outcomes if run as a secondary mission.

For the primary, you have the mission type and name at top, and the mission detail in the red banner with the campaign phase and the mission number. There’s some color text by the Loremaster and the date the mission began

[1], a quick overview of the general situation for command staff review, followed by a possible “opening scene” for the squad if they go on the mission — I’ve found this helps move play to the meat of the mission, though players are free to request free play scenes before this happens, or narrate a different approach.

Next, the mission goals are provided, written as the Commander might give to the squad, usually including what the best outcome is, what the minimum for success is, and often information that can be mined for more specific answers to Intel questions, including ideas for actions the squad could take, resolutions they might pursue, or things they must not allow to happen.

Following are three potential obstacles standing in the squad’s way: they describe what the problem is and how it is hindering them or preventing them from succeeding. There’s no need to feel tied to these, and not all three need be thrown at the squad, depending on how the fiction unfolds. When the engagement roll is a critical, players can narrate how the group overcomes one of these difficulties — I run that as GM’s choice, “Tell me how you overcame [specific obstacle]?” — and we come up with a new opening scene. I don’t necessarily run these obstacles as clocks (though you can with some), and often keep the obstacles separate from the clocks at the bottom of the sheet.

The clocks along the bottom of the sheet are of varying size, and I may or may not use them in play — they’re there to draw on as possibilities or for inspiration, or can be triggered by events in play. In some cases, though, they can be integral to the mission as given, such as time-limiting clocks. Even clocks linked to obstacles can be ignored, and the obstacle handled in some other manner (action rolls, fortune rolls, fiction, etc).

Finally, the last column on the primary provides some example complications the GM could use as consequences for rolls or as Devil’s Bargains to offer the players: greater danger, tough choices, and fiction-altering information!

Below that are a few questions the GM should(?) think about before or during play, which will uniquely shape the nature and elements of the fiction for each group, and (I’ve found) inspire a more robust narrative and visualization. They are also useful as prompts for the players, to see if they’re interested in a particular direction of play, or have ideas to further flesh out the world!

For the secondary, the sheet is split into sections based on the results of the engagement roll. These result outcomes also provide elements and details you can use to further flesh out the events, obstacles, and outcomes of the mission as a primary, but the details here (as with anything in BitD games) aren’t absolutes, merely possibilities to draw from.

[2]

Sometimes these sections also include a bit of post-mission detail about reactions and consequences, and may include an additional and optional minor boon or malus arising from that fiction — again, something that could also result on a primary mission outcome, depending on the fiction established in play.

Note that all these entries tend to build upon one another, rather than each giving a complete accounting: unless otherwise contradicted, one can presume the details hold true from one entry to the next.

The page begins with a bit of color by the Loremaster, which almost always specifically pertains to the ‘Critical’ result directly below it, and the end date of the mission. The text above the divider provides the details of how the result was better-than-good. Below that are the details of the ‘6’ success result. Note that for the text in the success result, it is never assumed that anyone in the squad dies: alter or add to the fiction here when the Marshal decides otherwise.

The next column is for the ‘4/5’ result, the top half if the Marshal chooses that the squad retreats, and specifically explains why they did so; the second detailing what happens if the Marshal chooses that the squad fights, including how two of the squad members died.

The last column is the what and whys of the squad failing to fulfill the objective, either through a ‘1-3’ failure roll, and how squad members were lost and injured, or through ignoring that mission and what the consequences of that decision are on the Legion or others.

Along the bottom edge, the benefits provided to the Legion upon succeeding are on the left, and the penalties for failure are on the right. I try to make certain these are concretely reflected in the fiction of the mission, rather than just being numbers.

Obviously, the visual elements of the mission sheets borrow heavily from the Band of Blades rulebook and playsheets, so I consider this to be Off-Guard Game’s visual IP, though the specific layout is mine. I want to be clear: this is fan-content for private use only and there’s no challenge here to OGG’s ownership or rights.

Since the first mission is taken directly from the book, I didn’t write up a sheet for it. I tend to consider that “Phase 0”, and the first set of missions the Legion is able to choose from to be “Phase 1”, taking place at the Western Front.

The following phase one missions were not the ones I used in the game, but from a prior game. For the first phase in this campaign, we ended up just adapting the Hozelbrucke Bridge mission, because I didn’t have anything prepared at the time. I’m including these here because they’re fun missions.

Phase 2 took place at Plainsworth, where the Legion spent a considerable amount of time gathering Intel and Supplies.

Phase 3 continued to take place in and around Plainsworth.

Phase 4 was the end of their time in Plainsworth. Two missions only this time as one mission was recycled from the prior phase.

Phase 5 took place on the Long Road as the Legion attempted to hurry across it to reach the mountains.

Phase 6 took place at the Barrak Mines, where the Legion stops to haggle for blackshot and pay respects at the tomb of an ancient chosen. I only rolled two missions for this phase, and one was replaced by a Special mission.

Phase 7 continued the Legion’s stay at the mines and St. Oysingra, with a focus on trying to delay Render’s advance.

Phase 8 brings the Legion onto the narrow paths and trails between the religious shrines of Gallow’s Pass wherein the Legion seeks artifacts and the blessings of the divine.

Phase 9 is a quick stop-over in the Talgon forest to seek out another artifact and gather more supplies in preparation of moving on to Fort Calisco.

Phase 10 cover the arrival of the Legion at Fort Calisco and their attempt to gain entry despite a besieging army.

[1] The dating system is our group’s design: each season is measured by its days, of which there are 90, and based on how the Time clocks fill, we decide the length of time over which the next set of missions occur. Each segment is, abstractly, around 9 days. The game starts late in the summer season already, however — we figure about 1/2 to 2/3rds of the way through the summer season (about 45 to 60 days) — so you may need to adjust your own summer dates and clock-tick periods accordingly.

This is not the official calendar or anything: your group should come up with your own way to handle this aspect, if you want to. Note: when the Time clock loses ticks, we simply had the next set of missions occur over a shorter term, and the following tick start earlier, so not to cause weird issues with the dates. (But we were also pretty loose with this, and didn’t think about or refer to the date more than a couple times, honestly.)

[2] I don’t necessarily recommend using the written secondary outcomes as the absolute fiction in your games, particularly if the players prefer to detail the results of what happened themselves (players are often more-than-happy to explain what happened, particularly if you can provide prompts using fruitful questions as needed, reducing the necessity for reliance on pre-written, canned results).